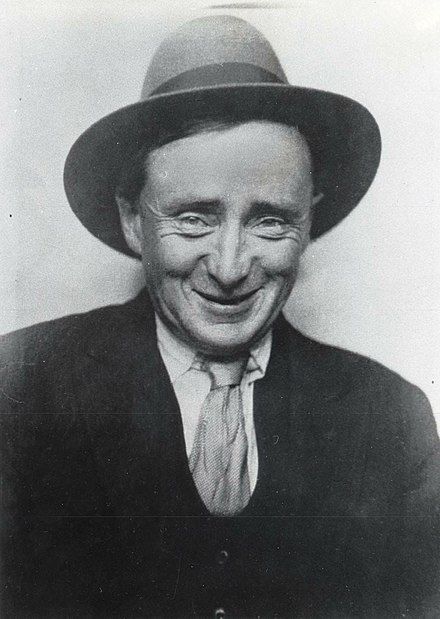

Pádraic Ó Conaire, Father of Irish Modernism

Note: this article was originally published on 28 February 2023, on my Substack newsletter, The Traveller’s Literary Supplicant.

By Christopher Deliso

Who was that, then? You might ask. A fair question. You might also be curious about how Pádraic Ó Conaire’s posthumous fate as Galway tourist landmark has commingled, oddly and until today, with that of a revered American president.

Today’s feature concludes a month of perfectly palindromic bookending birthdays; it began with my essay on James Joyce’s 141st birthday on the 2nd, and finishes with this tribute to a merry fellow author born on the far end of February, 1882.

Pádraic Ó Conaire arrived in this world on 28 February, in Galway, on Ireland’s west coast. Like Joyce, he’s been accused of spawning Irish modernist fiction.

The paradox resolves. While Joyce wrote in English, Ó Conaire wrote mostly in Irish. His influence on Irish writers (and the public) was immense, and he remains a beloved character there today.

However, for us ‘foreigners,’ limited translations into English means his insightful wit and storytelling mastery remain hidden. While new translations are out, even now most Youtube videos on the writer are in Irish.

Still, I’m sanguine that a review of his life and even one story will reanimate Ó Conaire for curious readers and travelers.

Influences: Raised by the Rugged Countryside and Its Language

The son of two publicans, Pádraic Ó Conaire (28 February 1882-6 October 1928), was born in a pub near the Galway docks. Orphaned at seven, he was raised by relatives in a Connemara village, in the Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area).

Thus, Ó Conaire grew up with an unusually good knowledge of the Irish language, and would be inspired by the spectacular, lonesome beauty of these stony coastal wilds. From this, young Pádraic took a love of nature and of the folk tales and idiosyncratic ways of the local peasants. Both would inspire his writing.

Studies, Life in London and Gaelic League Opportunities

Raised also by family in Co. Clare, the young man studied in Tipperary, before going to Blackrock College Dublin. Yet before his final exams he chose a civil-service job with the Ministry of Education in London, in 1899. There he kept involved with Irish affairs, joining the local Gaelic League.

This experience and locale gave Ó Conaire both a living and critical distance from his writing subject, Ireland. In this sense, he was like his fellow exiled Februarian Joyce over on the Continent. But his first-hand views of hardships faced by Irish émigrés in London added another element to his stories.

Pádraic Ó Conaire as Father of Irish Modernism

Despite the small Irish-language market, Ó Conaire had the times and key demographic on his side. He became the first person to successfully make a living writing stories and novels in Irish. His blend of realism, humor and keen observations of human nature was unique.

Ó Conaire’s ties with the London Gaelic League helped him teach Irish and publish in Irish-language media right away. His first story, ‘The Fisherman and the Poet,’ appeared in an Irish-language publication in 1901.

“Widely read and influenced by European literary models,” Galway historian Brendan McGowan notes, “Ó Conaire wrote in simple, direct Irish about the grim reality of life in contemporary Ireland, dealing with themes such as poverty, emigration, isolation, vagrancy, alcoholism, despair and mental illness.

Although he married in England and had children there, he also traveled in Ireland- famously, in 1915 to avoid WWI conscription by the British government. He taught and wrote in Galway and the Gaeltacht, thus keeping informed of the increasingly turbulent trajectory of events.

In 1916 the writer toured Ireland to assess the Irish language’s ‘condition’ for the Gaelic League. “While in Ulster, he was twice arrested – at least once for refusing to answer the questions of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in English – and was incarcerated in Armagh Gaol during the (Easter) Rising,” McGowan adds.

In his short life, Pádraic Ó Conaire was prolific, wrote an astounding 26 books, 473 short stories, 237 essays and six plays. His identity as the first Irish-language modernist was also affirmed in 2003 by scholar Angela Bourke, who singled out his 1910 novel Deoraíocht (Exile). The novel was a milestone in Irish-language literature for its realism and interest in social issues and the marginalized. The writer was honored similarly by scholar Philip O’Leary, in The Prose Literature of the Gaelic Revival.

However, today I’ll cover the more comic side of Pádraic Ó Conaire’s writing- his uniquely revealing and humorous craft, which avoids simplistic tragedy-retelling and instead creates something entirely new from even the most harrowing and combustible of collective disasters.

This great short literature covered is now available in English translation. My treatment is also instructive for how authors can deal with collective grief and transform the memories of collective events into an undefined, yet more peaceful and enlightened state that, while fictional mat yet also convey some truth.

Writers, I assert (based on this Irish example), can preserve the underlying humanity of people caught up in events too complex for any honest historian to narrate.

The Comic Genius of Pádraic Ó Conaire: Seven Virtues of the Rising

The above citation of Brendan McGowan is from his introduction to one of Pádraic Ó Conaire’s best-loved collections, Seacht mBua an Éirí Amach (Seven Virtues of the Rising), translated for the first time since 1982, by Diarmuid de Faoite.

“Arguably the first important fictional response to the Rising, the book secured Ó Conaire’s position as the foremost writer in modern Irish and the only one of international standing,” McGowan notes.

These seven stories recast the memory of a then-raw and traumatic collective event (the 1916 Easter Rising against British rule) in an unexpected and innovative way, for any language. Each story tells the tale of a different person connected, in one way or another, to the Rising. Yet the stories are fictional, neither histories nor simple apologia for the cause. From the shared context based on the failed revolt, what readers are given seems more like amusing morality tales, illuminating personal foibles and national myths.

Case Study: “The Bishop’s Soul” (Anam An Easpaig)

This great fabulist tale tells the (fictional) story of an unnamed bishop, based on the very real Bishop Edward O’Dwyer of Limerick (1842-1917). Already well-known and somewhat controversial at that time, he became even more famous after the Easter Rising by responding, in his 17 May 1916 letter, to that of British General John Maxwell in Dublin. Maxwell had demanded he discipline nationalist priest; O’Dwyer instead denounced the British handling of the Rising, executions of its leaders and deportation of other revolutionaries.

In the story, however, things are somewhat different. It begins on the evening of the Rising (before it has started), with the bishop sleeping in his broken-down car in a jacket, while his disgruntled driver tries to fix it underneath. They are somewhere in the countryside, on the road to Dublin (probably, Co. Meath). The bishop wanders off, his mind occupied with how to handle a British request to discipline a young priest with nationalist sympathies; the bishop is timid, and weighs his options. Meanwhile, the driver, having fixed the car in a foul mood, drives off, unaware that the bishop is missing.

The story-lines now diverge: the driver, trying to find the bishop on the dark road, instead finds an Englishman recently arrived in Ireland. They inquire at a roadside pub about the bishop, but are gone when the latter shows up there, after hours…

Of course, the locals in the illegally-operating pub are wary and, when the bishop (not wearing his religious garb) identifies himself only by saying, “it’s… me,” they barely let him in. Their suspicions seem confirmed when he requests not a stout, nor a whiskey, but only hot milk. (The arrival of a bishop in a pub would have been absurd, and the real-life Bishop O’Dwyer had been a celebrated Temperance movement leader before).

I won’t reveal the rest, as this and the other tales in Seven Virtues of the Rising are worth a read. Simply to say that the author does a masterful job of capturing the character of a historical figure during an event, and yet weaves a great fabrication out of it; such is the singularity of the character created that all we are left with is art.

Pádraic Ó Conaire’s Odd Immortalisation and Co-habitation with an American President

Considering Ó Conaire’s mastery of irony and wit, the multiple injustices suffered by his posthumous memorial in Galway are ironic and weird. This final vignette will also inspire literary travelers to Galway.

A short 1967 local media video, below, reinforces that Ó Conaire was beloved, both in his lifetime and long after. Following the death in 1928 of the writer, a man who “had loved people, had enjoyed a jar, enjoyed a story, and in turn was very much loved,” as the presenter says, the Gaelic League had raised money for a statue. The funds rolled in, and famed sculptor Albert Power (1881-1945) designed the monument. Éamonde Valera himself unveiled the statue of Ó Conaire, perched on a stylized Connemara wall beside a bird and a rabbit in Galway’s central Eyre Square.

For almost three decades, Ó Conaire enjoyed pride of place in the square’s center. Of course, the area would be much-visited by tourists and locals alike.

On 29 June 1963, one of these tourists, who also made a few comments in the square, was US President John F. Kennedy. (The JFK Library website has a photo here from that day). As the 1967 video here notes, the ill-fated president also received the Freedom of the City of Galway award.

Had Kennedy only lived, poor Pádraic (minus his Connemara ledge) would probably not have been “banished” to the square’s far side, to “a lavatory corner,” which turned out to actually be an electrical transformer. However, the new JFK monument had to go where he had been, in the square’s center, the authorities decided.

Indignant Galwegians complained in letters. In the end, after the Galway Corporation had heated debates with the Irish Tourism Board, a compromise solution was found. The writer (and his country ledge) were moved to a more central part of Eyre Square.

Near the end of the 1967 video, the presenter gets great comments from a town councilor, who says it had been hard convincing the Tourism Board to rescue the writer’s statue. The councilor, who as a child had known Pádraic Ó Conaire, recalls why the locals admired him so, and why they had developed such a sentimental attachment to his sculpted image.

However, the story gets stranger.

Under cover of dark in early April 1999, the statue was… beheaded.

The Irish Times, reporting then on the police’s recovery of the author’s limestone head, quoted the mayor as saying “this is Galway’s most famous landmark, and it is heartbreaking to see what has happened.”

The paper added that the monument, “was due to be moved as part of a proposed redesign of the square which includes a sculpture park.”

Another contemporaneous report reveals how the head was recovered, and identifies the culprits: “four youths from the north of Ireland were detained by Gardai in the city last night following a major search,” the article reads. “The four were arrested at Ceannt station, the city’s main bus terminus, after a tip-off. The group was about to board a bus to the north when Gardai swooped.”

After that, the original head and original statue of Pádraic Ó Conaire were reunited and moved to the safety of Galway City Museum’s lobby.

Finally, the archives of sculptor Powers were consulted, and after an identical copy was cast, following two years of work at a Dublin foundry, a bronze (and less behead-able) replica was unveiled in Eyre Square by the Irish president, Michael Higgins, reported RTE on 23 November 2017.

Although the media article does not mention it, that was of course also the 54th anniversary of JFK’s assassination. A rather interesting decision, to re-introduce the bronzed writer with the monument to the president who had supplanted him in 1963 following his own tragic death. Yet all’s well that ends well.

Excerpts from the original speech of President Higgins (himself, a former Mayor of Galway and representative of the region in parliament in the 1980s), officiating at the 2017 unveiling are in the video here.

Addressing ‘future generations’ of Galwegians, Higgins closes by rhetorically invoking the writer himself: “may they come to understand not only your literature, but also the profound humanism that was the heart of every part of your life.”