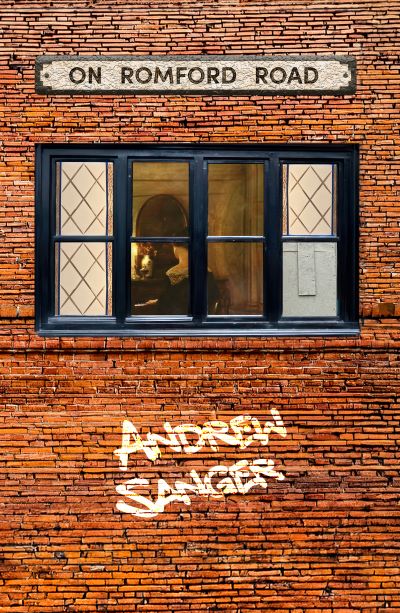

Book Review: On Romford Road, by Andrew Sanger (Focus Books, 2025)

Reviewed by Christopher Deliso

Andrew Sanger, On Romford Road (Focus Books, London, 2025; available in Kindle and paperback formats)

Overview

In his newest novel, veteran British travel author Andrew Sanger narrates a gripping, century-old family saga, from the perspectives of four generations of East-End London women. The story is set against the violent and murky backdrop of East London, from the First World War through to modern times, and chronicles an interfamilial vendetta and its unexpected consequences.

Very much in the Realist vein, accentuating the hardships and challenges of local life, Sanger’s prose is also tinged with an irrepressible Romanticism. He seeks to illuminate the better side of people, even (and, especially) when subject to harrowing challenges and stresses. While On Romford Road essentially plays out a central theme over generations, it does provide, from another viewpoint, a companion to the eclectic and evolving social history of East London and indeed, another perspective on major changes in British social life, customs and norms over the past century.

About the Author

British-born Andrew Sanger is a well-traveled author of many articles and over 40 travel guides, with a special interest in France. In addition to On Romford Road, he has also published four novels since 2009, often (as with the current one) having a special focus on aspects of Jewish heritage and culture. Read more about the author and his works on Andrew Sanger’s official website.

Structure of the Work

Sanger divides On Romford Road into four parts, each named after a different woman in the family (Harriet, Maud, Elizabeth and Alex). This has the benefit of a clear and continuous structure, and the disadvantage that the reader knows from the beginning that at least some characters must survive their crime-infested environs. As the plot thickens, this leads the attentive reader to imagine at least three plausible scenarios; I will not give any plot spoilers, except to note that I guessed correct on two final outcomes. Indeed, the very structure of On Romford Road is both a point of plot novelty and a limitation; in the end, Sanger is telling ever-enriched versions of the same story, compounded over time. This makes it seem the characters are more archetypes than individuals. Given the page count (around 300pp.) and century of coverage, there is not really adequate space to develop most of them.

Plot

On Romford Road starts with a dramatic scene at the Well Smack Inn, a local fixture of a pub with cellars of medieval origin. Here, the publican, Ted Cotter and his piano-playing wife, Harriet are temporarily hiding a Russian-Jewish émigré family, the Zuckermans; nationalist mobs led by local criminal Charlie Sleet torch the émigrés’ sweetshop and other East-End premises of presumed German ownership. The explanation given is that this is revenge for the German sinking of the Lusitania.

Mr. Cotter is seriously injured by Sleet in front of his little daughter Maud, but later on he leads the Zuckermans to safety, in a feat of exertion that hastens his own demise. While the mob has temporarily dispersed, Harriet Cotter decides to take preventative measures against Sleet by requesting aid from a regular police visitor to the pub. Here the reader is made to understand that even in the ‘old days,’ police and publicans exchanged favors such as free food and drink in exchange for information. Of course, what the widow Cotter has in mind stretches the bounds of this usual tradition, and the only inspector who will help her guarantee her safety against Sleet, it turns out, also seeks to remarry her and take over the pub.

To avoid giving away further plot spoilers, I will avoid going into great detail about the various plot points that lead the Zuckermans back into the lives of Harriet and her family, and that expedite the rise of the Sleet crime family. Sanger does provide some clever turns of history, such as the Second World War, to bring new dynamics into the inter-familial relationship. There, in the desert of Egypt, Len Blake (husband of the grown-up Maud) turns out to be the British military’s commanding officer to Mickey Sleet, son of Charlie Sleet. As a fellow writer, it is interesting to observe how Sanger chooses to develop his characters in different settings. In Egypt, for example, both men survive by using the cunning and street-smarts of East London, in a foreign hostile environment, against both a common external enemy and each other.

The plot continues following the war to the consolidation of the Sleet family through inter-marriage with two other families—something that does not fail to affect the book’s main heroines—and the birth of Maud’s daughter, Elizabeth, who goes on to become a barrister at a time when few women had yet been able to achieve this. Elizabeth herself eventually takes part (with her husband, Bernard) in prominent legal cases targeting, of all things, police corruption. This too fits with historical events, the somewhat unknown to non-British Operation Countryman (1978-82), in which rural police were called in to investigate London Metropolitan Police extortion and corruption. Elizabeth’s reason for this interest is given ideological origins but never fully developed. This is problematic because the rightful paranoia about the Sleets of her mother and grandmother, both laconic by nature, was never really explained to her.

From the point of view of the criminal family, who are portrayed as violent, thuggish and unpredictable, everything is ultimately about business. However, while the predictable transition from illegal to legitimate business happens during the book, it takes a longer time and more extreme resolution than should be the case if these people were in fact as capable as they are said to be. The lack of explanation makes later events somewhat implausible, or at least requiring somewhat more discussion.

Further, any novel covering almost a century of events inevitably uses many ancillary characters. Some of these are thrown by the wayside when their roles are finished. By the same token, some peripheral characters are insufficiently fleshed out in advance of their appearance (for example, two aspiring female assassins who play a key role toward the end). Nevertheless, Sanger does an admirable job of stitching together the fates of the various main characters and their legacies in a single comprehensive vision designed to make a statement about diverse approaches to survival in the historic East End. For regardless of who the individual characters and generations may be, this attribute seems to link them all.

The final part of On Romford Road concludes with the upbringing of Alexandra, the daughter of Elizabeth and Bernard. A piano prodigy from an early age, Alex seems to have inherited this gift from her great-grandmother Harriet—whose barroom piano has in the meantime been recovered. The interrelated resolution of the East-End families, relationships and careers are cast against an ever-shifting background of change in London and Britain generally.

Additional Aspects

Beyond its existence as a straightforward Realist novel, On Romford Road is distinguished for its historical and social-life aspects, as well as descriptive elements. The author has clearly done his research and weaves in both the well-known historical background (such as the sinking of the Lusitania in the First World War, and German bombing of London in the Second World War), with less-remembered but important details like new motorways, legislative changes, and Operation Countryman.

Sanger’s chosen settings, ranging from London to other British towns and the Spanish and French Mediterranean, also reflect his personal and professional experience and as such are well described. Although an argument could be made for perhaps absorbing the Geographic Note (about the Roman-to-modern prehistory of the Romford Road) into the general text, in either case the author succeeds in articulating that this stretch of London has for a very long time been associated with misfortune, crime, poverty and bleakness—though, on the other hand, it can have its bright spots, ranging from helpfful locals to the riverside to music halls. Through to the final pages, Sanger’s project seems to be concerned with reinforcing the cyclical evolution of change as recurrence of previous dynamics, as new generations of outsiders and immigrants seeking to make their fortune enter the space occupied by the ancient road.

Conclusion

There is much to admire about On Romford Road. For mystery and crime fans, it brings elements of underworld crime over generations, murder, corruption, rackets and legal casework loosely based on actual events in 20th-century London. For readers of social and cultural history, the coverage of Jewish history in London, the developments in unions, feminism, and various reforms are interesting, as is the well-researched and ever-changing image of the East End over a century’s time. Indeed, it is perhaps Sanger’s detailed research, personal knowledge and travel descriptions that make the book most unique.