The Genius of G.K. Chesterton: How Borges Led Me to “The Blue Cross”

Note: the following essay was originally published in two parts in April 2023, on my Substack newsletter, The Traveller’s Literary Supplicant.

By Christopher Deliso

Part 1

Recently, the television offered yet another modern detective series: the BBC’s Father Brown. After watching, I was unsurprised when the Internet confirmed that the 10-year series is only “loosely based” on the original Father Brown mysteries by G.K. Chesterton. The show seemed somehow derivative of Midsomer Murders, but lacking the wry humor of either actor John Nettles in the latter series, or of the humorous writing of Chesterton’s classic stories: in short, an indecisive series marred by anachronisms and the forcible inclusion of modern social issues to a period setting that was not even the original period of the author, as this critical article explains.

Yet production compromises aside, all publicity is good publicity, and if the current BBC effort leads more people to read Chesterton (as the previous ITV 1974 series did, and even Alec Guinness’s first film portrayal of the priestly detective did in 1954), than so much the better.

I’m just a bit cross because G.K. Chesterton and his writings never entered my consciousness until a few years ago, when I started to take a new interest in detective stories- and even then, only accidentally. These wonderfully-written tales were never a part of school curricula, reading lists, nor recommended by anyone. And that is a shame because, while there are many authors of detective literature, most do not qualify firstly as authors of literature.

Chesterton is different. He is what we call a ‘real writer,’ as Jorge Luis Borges might have said.

How Borges Introduced Me to Chesterton

A few years ago, I discovered this Open Culture article, which states that in 1985, “Argentine publisher Hyspamerica asked Borges to create A Personal Library — which involved curating 100 great works of literature and writing introductions for each volume.”

As one of my longtime favorite authors, and one of the most subtle and discerning intellects of the 20th century, Borges and his Personal Library were of course immensely interesting to me. Although he made only 74 selections before his death, Borges did provide a predictably eclectic list of texts ranging from poems and short stories to scientific and sociological works to the Bhagavad Gita, Histories of Herodotus, tales of Edgar Allan Poe, and The Decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Although his entries were ordered numerically, there is no indication that this refers to order of preference.

Despite all the exotic abundance of unknown titles on the list, the one that jumped out at me for some unknown reason was number 5- The Blue Cross: A Father Brown Mystery, by G.K. Chesterton. I had never heard of either the story or the author but felt compelled to learn more. I found the story easily enough; and, even better, an exemplary narration by British voice actor Simon Stanhope, on his YouTube channel BiteSized Audio Classics. (I’ve previously highlighted Simon’s readings in the TLS newsletter, and his rendition of the story will be provided in the second part of this essay for your listening pleasure).

The Borges-Chesterton influence was recorded well before Borges even took on the ‘personal library’ challenge in 1985. He had singled out Father Brown as a source of inspiration in his own works, decades before that. This means that the addition of “The Blue Cross” to the 1980’s list does not represent an inclusion made late in life, but should rather be understood as an enduring favorite which Borges would not fail to commemorate in his final reflections on literature, with that Number 5 listing.

Robert Gillespie’s Contribution to the Case (1974)

Before moving on to Chesterton himself, let me acknowledge some scholarly writing on Borges and Chesterton, as it will demonstrate the long-existing nature of this point of reference.

An article by scholar Robert Gillespie (“Detections: Borges and Father Brown,” in NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 7, No. 3, Duke University Press, Spring 1974) gets to the origins of the influence, and considers it from more points than I can relate briefly. (It is worth reading for anyone with a serious interest in either author). Gillespie cites a book by Borges I have not yet read:

“In Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952, Jorge Luis Borges affectionately mentions G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories and hints that along with Poe’s they are influences on his own stories of mystery, crime and detection.”

A brief bibliographical note.

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 was translated into English by Ruth L.C. Simms and published in the University of Texas Press’ Texas Pan-American series in 1964. Borges’ original Spanish version was published in 1952 as Otras inquisiciones (1937-1952) by SUR, and if you read Spanish, it can be found on Amazon here.

Gillespie first proposes that a better understanding of Borges’ stories lies in “looking at Chesterton’s priest, the way both authors experiment with conventions of the mystery genre to examine the supernatural and the nature of evil.” These are all eminently reasonable suggestions and, along with the fascination of both writers with paradoxes, microcosm-macrocosm and the nature of reality, make for good points of investigation.

It may be an accident of history that Chesterton’s detective resembled in some ways the reserved, shy Borges himself. For Gillespie, the ‘unprepossessing’ and ‘dough-faced’ detective of Chesterton’s imagination appealed in his singular plainness to Borges: “the perfect figure for the butt of a joke, Borges sees Father Brown is also the perfect figure for getting in the way and solving metaphysical jokes.”

Another point that would have fascinated Borges, coming from a Catholic country like Argentina and perennially focused on competing explanations of rationality, myth, religion and philosophy, was Chesterton’s authorial choice of a Catholic priest for his protagonist. However, he is no ordinary one. Gillespie has this to say about Father Brown:

“He works by reason and faith, and the two are never at odds owing to a middle sense, intuition, which keeps him from acting mistakenly even if truth is not revealed to his intellect: he has a mystic’s cloud on him when evil is near.”

This subtle integration of faith and reason with an arbitrating ‘middle sense’ of intuition is a fantastic innovation in the history of the genre. It might not be completely unique to Chesterton, as (aside from the plenitude of ‘psychic detectives’ out there), it could be argued that Christian hagiography (both Western but especially Eastern Orthodox) incorporates intuition on the parts of saints or blessed souls to solve otherwise seemingly intractable and baffling mysteries.

Father Brown as a literary character also takes on a sophistication that exceeds that of more famous literary detectives, just owing to his life situation. Gillespie cites this as well. Thus, while being a celibate priest adds to Father Brown’s remoteness from common human experience, Gillespie points out that the character is still “thoroughly a gentleman,” and points out that “the traditionally distinguishing features of the gentleman – power, rationality, and responsibility – mingle in Father Brown with the spy’s invisibility and unreality.”

The last of these, ‘unreality,’ would certainly have captured Borges’ attention, and we will see that all of these character qualities make their appearance in key moments in “The Blue Cross.”

Further, Father Brown’s love of “obscure, unique oddities and trinkets make him a perfect Borgesian character,” the scholar notes.

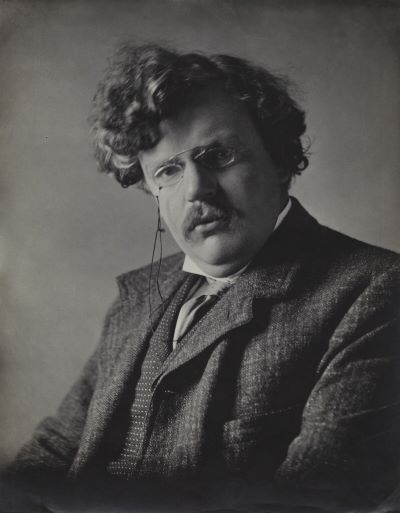

Who Was G.K. Chesterton?

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was born in London. His father, Edward, was an estate agent; his mother, Marie Louise (Grosjean) was of Swiss-French ancestry, a factor that certainly played a role in Chesterton’s later affection for French culture which, in combination with his friendships with figures like the Catholic novelist Hilaire Belloc, influenced both the direction of his Christian faith and the esprit of his literary characters. A talented visual artist, Chesterton attended art school but turned to writing instead, working as a London newspaper columnist after the turn of the century. In 1901 too he married Frances Blogg, a devout Christian, who also influenced his Christian beliefs strongly.

Chesterton had started out by working for two London publishers between 1895 and 1902, before quickly becoming prominent for his own columns and books. He had a great wit and sense of humor, and with his tall, bulky and cheerful manner was instantly recognizable. In an extraordinarily diverse career of over 30 years, Chesterton would pen thousands of newspaper articles, several plays, poems, treatises on writers from St. Thomas Aquinas to Charles Dickens, Christian apologetic texts, and novels that imagined a future London (The Napoleon of Notting Hill, 1904) and comic-metaphysical thrillers (The Man Who Was Thursday, 1908). During the last four years of his life, Chesterton was also a popular host on BBC Radio.

However, despite all of his contributions to philosophy, theology, literary criticism, social and political debate and so on, today it is the detective stories of ‘the little Essex priest,’ Father Brown, that have best endured. There are several possible reasons for this – aside from the statement that everyone loves a good detective tale – though I believe there is a certain reason for why Chesterton’s genre fiction resonated so well with readers, many of whom do not share his acquired (1922) Catholicism.

Part of this appeal is perhaps because Chesterton’s unique style is sufficiently idiosyncratic, borrowing from such diverse influences, that it tends towards discursive statements that test the established rules of everything but fiction. While above all, Chesterton is a lover of humanity despite all its fallibility, his merry tendencies to throw together everything – the painter’s visual symbols, the evangelist’s allegories and parables, the logician’s neat traps of contradiction – that he sometimes comes across as baffling. Is he being a philosopher, or just a sophist- or is he just having a laugh at our expense?

An indicative textual example (not from the detective series) refers to one of Chesterton’s famous intellectual friends, of which he had many. A charming and very English characteristic of Chesterton’s was his zeal for debate and the allowance for agreeing to disagree- a rare enough concept today.

Thus, though they often disagreed, Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw were good friends and enjoyed debating. Here is an example of Chesterton’s unique logic, at Bernard Shaw’s expense, taken from his first major Christian apologetic book, Orthodoxy (1908). Chesterton argues:

“The worship of will is the negation of will. To admire mere choice is to refuse to choose. If Mr. Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, “Will something,” that is tantamount to saying, “I do not mind what you will,” and that is tantamount to saying, “I have no will in the matter.” You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular.”

Tracing Father Brown: All Roads lead to Tipperary

The very first Father Brown story actually appeared in the US, in The Saturday Evening Post, on 23 July 1910, under the rather too obvious title “Valentin Follows the Curious Trail.” This was reprinted in England as “The Blue Cross” in the September 1910 issue of The Story-Teller. In 1911, it was the lead story in Chesterton’s first full collection of detective stories, The Innocence of Father Brown.

The story introduces not only Father Brown, but also Paris police chief Valentin, a master puzzler of the most difficult cases, and his nemesis, the gentleman-thief Flambeau, a master of disguises who can conceal everything except his great height (like Chesterton himself, Flambeau is six-foot-four).

But what was the inspiration for the character of Father Brown? While commenting on the current BBC series, the Birmingham Post related that Chesterton’s close friend (and one of the key people behind his Catholic conversion), Fr. John O’Connor of Bradford, was the basis for the character. He was a close friend of Chesterton’s from 1904 on. And this native of Clonmel. Co. Tipperary was not shy about the connection, even citing it in his 1937 autobiography, the year after Chesterton’s death.

The article states that “O’Connor is the subject of a biography – titled ‘The Elusive Father Brown: The Life of Monsignor John Joseph O’Connor’ – in which author Julia Smith suggests that his encounters with poverty in Victorian Bradford were an important influence on Chesterton’s Father Brown novels, according to the Bradford Telegraph and Argus.”

The priest was apparently “horrified by the scenes of poverty and vice he encountered in Bradford’s slums. Chesterton, too, was taken aback by his friend’s reports of his experiences and subsequently drew on them for inspiration,” the story relates.

In this concern for social justice and poverty, Fr. O’Connor bore similarities to contemporaneous Irish authors like Pádraic Ó Conaire (covered by the TLS here) and the playwright Sean O’Casey, whose depictions of the paradoxes of war, nationalism and urban poverty characterize his literary vision.

The historical figure of Fr. O’Connor and his post-1904 friendship with Chesterton is also important in another way, as it reveals the author was not simply trying to ‘invent’ a new type of detective at a time when doing so would be entirely expected: in the increasingly competitive and varied Golden Age of the mystery and detective fiction era, new characters and concepts were coming out frequently (as we have already discussed while covering L.T. Meade and her collaborators).

In Chesterton’s case, an unsuspecting author befriended an Irish priest who had both the street knowledge and intellectual acumen to make the whole idea plausible. He had studied at the English Benedictine College at Douai in Flanders, and then did philosophy at the English College in Rome. Said to have had a great intellect, Fr. O’Connor was a good conversationalist who could keep up with Chesterton’s rapid wit and indeed, and spark his imagination.

Aside from the Irish influence on Chesterton’s fictional ‘Essex priest’ this historical anecdote demonstrates how a specific case of an actual clergyman’s pastoral outreach provided harrowing ground-level insight to the sophisticated literary urbanite Chesterton. If not the source of all the author’s actual ‘research,’ Fr. O’Connor might well have been partly responsible for stoking Chesterton’s zeal for analyzing the tragic, the sinful and the simply misfortunate events of human nature from a composite theological and psychological viewpoint.

Part 2

Today’s concluding part is concerned with language, seeking to provide a close analysis of the plot and particularly, Chesterton’s marvelously unique writing in “The Blue Cross” (with some unexpected anecdotes from literary history emerging too).

The essay’s final reward, as promised, is the link to an exemplary audio performance of the story by English voice-actor par extraordinaire Simon Stanhope, owner of the YouTube channel, BiteSized Audio Classics. (If you’re on Bandcamp, visit Simon’s Father Brown album page there for recently re-recorded takes on five other Chesterton classics).

“The Blue Cross” as a Literary Work (Spoiler Alert!)

If before my exegesis you’d like to enjoy the story ‘cold,’ then read it here, or listen to it at the YouTube page at bottom (almost an hour’s listen). Otherwise, let us now begin.

Plot summary: The super-sleuth of the Continent, Parisian police chief Aristide Valentin, travels to England on the trail of Flambeau, suspecting that the cunning international thief will be casing out a clerical conference in London for its valuable ecclesiastical treasures. After crossing the English Channel and getting on the train, Valentin overhears – and reprimands – a simple-minded little priest who has told a woman he’s caring for a valuable silver cross studded with blue jewels…

The priest, of course, is Father Brown, but since this is the first story in the series, his importance is known to neither the (original) reader nor to Valentin- which makes it a unique (i.e., non-repeatable) aspect of the plot and thus unique within the future series. This fact might help explain why this particular Chesterton story so appealed to Borges.

From here, Chesterton begins the major structural innovation of the story: the inversion of events, which in turn opens up philosophical discussions of causality as variously argued.

Whereas typical genre stories feature a detective searching for clues to solve a crime that has already taken place, in this story, the detective is confronted by an illogical series of odd events, clues perhaps, but no crime to be investigated.

At the story’s conclusion, when Flambeau at last is caught out, it becomes clear that Father Brown has surreptitiously orchestrated the set of odd events in order to keep Valentin on the track from an advance distance. It is both an ingenious ruse for an accidental, peripheral assistant-detective, but in other ways a metaphor for the presence of the Divine in human affairs. It is an affirmation of the sort of everyday miracles that Chesterton fully embraced in his theological works.

The extraction of meaning and reassembly of logical order from the apparently disordered series is the triumph of reason. And this is essential, for both the story and again, for Chesterton as a thinker: “you attacked reason,” Father Brown tells Flambeau, when explaining how he knew the disguised thief was not really a priest. “It’s bad theology.”

The Entertainment of Accumulated Clues

The peregrinations of Valentin around London comprise the bulk of the story. This is used by Chesterton for entertaining with examples of causality; Father Brown has a preternatural understanding of Valentin’s singular process of deduction, and so creates a series of apparently meaningless events in the manner that would be of meaning to only this French detective.

Thus, at a restaurant where the sugar and salt containers have been mischievously switched, Valentin is told that the odd stain on the wall was left by two priests. The waiter informs that the shorter one (whose description Valentin matches with that of the priest on the train with the silver cross) had flung his soup at the wall before abruptly leaving.

The trail across London includes similar shenanigans at a greengrocer’s, where Valentin learns the short priest switched signs, and upset an apple cart. The detective enlists two London policemen and continues to another restaurant, disfigured by a star-shaped crack in its window; he learns from the waiter that the short priest had overpaid and when asked what the ‘tip’ was intended for, stated that it was for the window he was about to break, before merrily breaking it and rushing off again with the tall priest.

Then, the proprietress of a sweets shop relates to Valentin that the two priests had been there as well- the shorter one having returned to say he’d forgotten a parcel and asking for her to mail it if found, which she did. Valentin and the policemen finally find the two priests as dark approaches, on Hampstead Heath, and lie in wait while Father Brown engages in a theological discussion, and then tells Flambeau that he has recognized him as a thief. Flambeau believes he has already stolen the parcel from the apparently simple priest, but is wrong, the real cross having already been sent safely by the woman at the sweets shop.

Having executed his duties and accused Flambeau of “bad theology,” Father Brown states that he is aware three policemen are near – for he himself has led them there, with his trail of odd clues – and that there is nowhere to run. Flambeau makes an elegant grand bow to Valentin, ever the sport and the showman, but the Parisian policeman defers the credit, as Father Brown blinks around like a mole, ever modest and inaccessible.

Chesterton’s Vision of a French Detective and Stylistic Innovations

Early on in the story, Chesterton describes Valentin in a unique way that draws on his readings of Voltaire, Poe, Belloc plus other personal and literary experiences. What is interesting is to note, as I mentioned in the first part of this essay, how aspects of his philosophical and non-fiction argumentation converge in his fictional prose, coupled with references to genre developments at the same time Chesterton was trying to break into the business.

As such, he describes Valentin thus:

“Aristide Valentin was unfathomably French; and the French intelligence is intelligence specially and solely. He was not “a thinking machine”; for that is a brainless phrase of modern fatalism and materialism. A machine only is a machine because it cannot think. But he was a thinking man, and a plain man at the same time.”

Here we must note that Chesterton (whose story was appearing in 1910 in the Saturday Evening Post) was taking a shot at an established Post writer of detective stories, American author Jacques Futrelle, whose character Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dussen was indeed nicknamed ‘the thinking machine’ for his application of pure logic to solve cases.

This chess-master character first appeared in the 1905 story, “The Problem of Cell 13” (in The Boston American), and was reprinted in a book of detective stories entitled The Thinking Machine in `907.

As always with Chesterton, his criticism was not personal but philosophical, and perhaps he would have not included the Thinking Machine reference had “The Blue Cross” been published two years later than it was.

That is because Futrelle was last seen alive, stoically smoking a cigarette with John Jacob Astor, on board the sinking Titanic, having forced his wife Lily to get into a lifeboat.

As is so often the case when it comes to literature and the people who make it, you could not make this stuff up.

Continuing his description of Valentin, which is designed to carve out a new persona for a detective capable of inhabiting his own thought-world, Chesterton adds:

“All his wonderful successes, that looked like conjuring, had been gained by plodding logic, by clear and commonplace French thought. The French electrify the world not by starting any paradox, they electrify it by carrying out a truism. They carry a truism so far—as in the French Revolution. But exactly because Valentin understood reason, he understood the limits of reason. Only a man who knows nothing of motors talks of motoring without petrol; only a man who knows nothing of reason talks of reasoning without strong, undisputed first principles. Here he had no strong first principles. Flambeau had been missed at Harwich; and if he was in London at all, he might be anything from a tall tramp on Wimbledon Common to a tall toast-master at the Hotel Metropole. In such a naked state of nescience, Valentin had a view and a method of his own.

In such cases he reckoned on the unforeseen. In such cases, when he could not follow the train of the reasonable, he coldly and carefully followed the train of the unreasonable. Instead of going to the right places—banks, police stations, rendezvous—he systematically went to the wrong places; knocked at every empty house, turned down every cul de sac, went up every lane blocked with rubbish, went round every crescent that led him uselessly out of the way. He defended this crazy course quite logically. He said that if one had a clue this was the worst way; but if one had no clue at all it was the best, because there was just the chance that any oddity that caught the eye of the pursuer might be the same that had caught the eye of the pursued.”

These paragraphs alone illustrates what I stated in this essay’s first part: that Chesterton is not a writer of detective literature, he is a writer firstly of literature. All of the features of the logical and poetical argumentation that are found in his other types of writing are combined here, in new ways and toward a new purpose. At the same time, they continue to support his general theological and epistemological position. In Chesterton, we see detective fiction elevated to the position of philosophical literature.

Chesterton’s Contribution to the Genre

And this is very important to note. When approaching what was to him a totally new genre, detective fiction (by 1910, a fairly well-trodden path), he did not need to invent gadgetry or novelty characters- though that was very much what many others in the genre were doing for simply market purposes. Chesterton brought something unique to the genre simply by remaining his own man.

The fact that he has a priest for a peripheral detective is thus actually the least remarkable element here. Rather, the fact that he brings over rhetoric, knowledge and stylistics from completely different genres and somehow makes them work in what had previously been a fairly uniform genre is what makes “The Blue Cross” so special. Had Chesterton never written another detective story, it would still be as valuable as it is to literary history.

Structure and Imagery

Chesterton was a painter and most of his mysteries involve strong visual images that are also symbolic, generally with some philosophic or spiritual dimension to them. And he weaves this into his narrative in ways that have structural sense. For example, the beginning and end of “The Blue Cross” have the same recurring motifs of color into his overarching structure. Take the opening line:

“Between the silver ribbon of morning and the green glittering ribbon of sea, the boat touched Harwich…”

That opening line alludes to the blue cross as a physical object, and starts the description of Valentin’s arrival in morning. Later, near to the final scene on the hill, it has become evening; along with the predictable, daily inversion of time, the color motif is repeated in a new setting, and reflected in metaphysical confirmation informed by reason, as Valentin and his colleagues gather in the dark to overhear a strange theological discussion between the ‘two’ priests:

“They did not find the trail again for an agonising ten minutes, and then it led round the brow of a great dome of hill overlooking an amphitheatre of rich and desolate sunset scenery. Under a tree in this commanding yet neglected spot was an old ramshackle wooden seat. On this seat sat the two priests still in serious speech together. The gorgeous green and gold still clung to the darkening horizon; but the dome above was turning slowly from peacock-green to peacock-blue, and the stars detached themselves more and more like solid jewels.”

Again, this is the sort of ‘real’ writing that fascinated readers like Borges, and which helps draw the story together from a structural perspective. No wonder Borges loved it!

I could go on all day about neat turns of phrases, comic jests, and other ‘Chestertonian’ elements of the story, but I think it’s rather enough. Better to just let you enjoy the story.

So, thanks for reading, and please enjoy “The Blue Cross” as narrated by Simon Stanhope on his BiteSized Audio Classics channel.